Criminalisation confronted

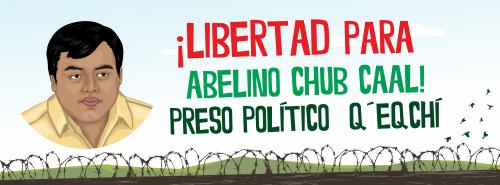

The historic victory of 26th April, when Abelino Chub Caal was acquitted of all the malicious charges brought against him, has highlighted the ongoing struggle for indigenous rights in Guatemala. Despite being a majority of the population within the country, indigenous people are discriminated against in every area of life.

A recent report, Situation of Human Rights in Guatemala (IACHR, 2017), provides a bleak picture of the predicament of human rights defenders. Murder, intimidation, criminalisation and stigmatisation are all tactics used to repress those demanding rights for disadvantaged groups. During 2018, 391 human rights defenders came under attack, including 147 cases of criminalisation and 26 assassinations – one killing every two weeks (UDEFEGUA, 2019).

In January 2019, President Morales ended an agreement with the United Nations that established the CICIG (International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala). This commission supported the Attorney General to pursue corruption and illegal groups that promote impunity. The termination signalled an even greater repression of human rights and an increase of those under attack.

One outstanding example of a human rights defender who has suffered from such attacks, including attempted murder, is Abelino Chub Caal. Abelino is a Mayan Q’echqi’ community organiser working with the Guillermo Toriello Foundation (FGT). He dedicates himself to promoting rural development and protecting the rights of communities whose land is under threat from large-scale commercial landowners and agribusiness. Abelino was held in pre-trial detention and denied bail, on unsubstantiated charges, for more than two years from February 2017. The judicial process was delayed and delayed, until his trial opened on 22 April 2019.

Abelino’s case exposes the injustices that have been perpetuated since the formal end of Guatemala’s civil war in 1996. It also highlights the struggles of those who are committed to ensuring that rights for all are finally won, despite the repression.

Dispossession and eviction

As part of the 1996 post-civil war Peace Accord, a process was established to secure land rights for indigenous people. But since then attempts to register land have been obstructed and indigenous communities have been increasingly dispossessed. The expansion of monoculture plantations for African palm and bananas has led to violent evictions of indigenous communities.

It is in this context that Abelino Chub Caal, working for over a decade with community-based organisation Fundacíon Guillermo Torriello, was supporting indigenous communities in the Polochic Valley of north-eastern Guatemala. An agribusiness company took aggressive action against indigenous communities in El Estor. The company wants to consolidate five farms into monoculture plantations on land they claim is private property.

Already by 2011 Abelino had become known as a defender of indigenous rights. By exposing illegal activities he had also become targeted as an adversary of big business interests. He experienced the murder of colleagues, physical attacks and increasing levels of threats. Despite this, according to Abelino’s wife Estela Cucul, he is:

"someone who has always been in meetings, in dispossessions so that they do not take property away from people, in the dialogues always on the side of the communities. Abelino … has helped the communities to not fight against each other. When there is help, he seeks for it to be given to everyone. Abelino walks hours to go wherever they need him."

Working with FGT, he has supported communities with development initiatives, sustainable agriculture and protection of their land. He has mediated conflicts and pursued solidarity when communities were under threat. As a recognised mediator, Abelino has taken part in many meetings as part of a central government sponsored initiative intended to avoid violence and reach negotiated settlements between commercial landowners and indigenous communities.

In October 2016 several police officers were injured in the violent eviction of Esperanza Tunico village. COPREDEH, the official Guatemalan government human rights agency, called Abelino for support. FGT didn't work directly with that community at the time, and the invite presented considerable personal risk to Abelino. Nonetheless he mediated in the dispute, preventing further evictions of other nearby communities. In January 2017 Abelino also intervened for the release of several police who had been held by community members in a different dispute.

Abelino was also involved in mediating a conflict at Plan Grande, an indigenous community. The community was recorded as being established as far back as 1884, but in an area irregularly registered as private property. The land is claimed by the same company that evicted Esperanza Tunico. This community had already sought to resolve their land issues by buying land from the previous ‘landowner’. However, this new claimant wants to build a dam on the site and so has sought an eviction order against them and other villages. As expert witnesses have testified, indigenous land rights are invisible at the state land registry – officials register land acquisitions for large ‘landowners’ and companies on request without verification of existing indigenous rights.

Although there is an ongoing formal investigation to determine the ownership of the Plan Grande land, Abelino was viewed as an obstacle to the established business interests. Attempts to buy Abelino off with money, a job and a car failed. Abelino responded,

"I have learned from the communities that dignity is not sold. You cannot negotiate our dignity or the land."

So a different approach was taken.

Malicious prosecution as a strategy

A common strategy to neutralise opposition is malicious prosecution to criminalise resistance. Very serious charges are made, requiring defendants to be held in custody even when there is no credible evidence. Cases can drag out for years before they come to trial.

As a colleague from FGT observes,

"The public prosecutors arrive, the large landowner tells them their allegations and they take it as truth. The Prosecutor’s Office and Court in Puerto Barrios have been coopted by businessmen."

Dozens of arrest warrants are then issued. The warrants can be activated at a critical point, to disrupt communities’ resistance to dispossession and eviction.

In this short video Claudia Samayoa, founder of UDEFEGUA (Human Rights Defenders Protection Unit Guatemala) examines criminalisation, “the unlawful use of the criminal justice system.”

On 4 February 2017, as Abelino was in a restaurant with his family, he was arrested. He was accused of aggravated robbery, arson, illicit association, use of coercion and belonging to illegal armed groups. The arrest warrant had been issued back in October 2016 when Abelino had been involved in defusing the violent situation at Esperanza Tunico, although he had not been present or involved when the violence happened. The warrant had been held back for an opportune moment.

Since his arrest there had been no credible evidence resented and the prosecutor’s office had even requested that the case be dismissed. Regardless, he was held in prison for more than two years and moved to Guatemala City. Pre-trial hearings were delayed or abandoned, none of which managed to establish whether there was a substantive case to answer or not.

Abelino’s trial eventually started on 22 April 2019. As was already clear, the ‘evidence’ against him was non-existent. He was not present on the contested land on the date he was accused of promoting violence and arson. Witnesses gave contradictory evidence and the maps and titles produced by the company were shown to be irregular and inconsistent.

In judgment the court highlighted the way the law was used to criminalise and the manner in which the land registry is manipulated. The company had from the start assumed their accusations would be accepted without question. What made the outcome different this time was the scale of organisation to confront this injustice. A broad coalition of community-based and international organisations threw a spotlight on this case, raising petitions and mobilising on social media.

Fighting back

The continual arrest and harassment of community leaders and advocates is intended to prevent communities from claiming their constitutional rights and deprive them of the support they need.

Despite the increasingly repressive context, FGT and partners have pursued a multi-dimensional response. This consists of ongoing research on land ownership; to provide the expert evidence that communities need to defend their land rights. There is also outreach to national, regional and international organisations; to publicise cases like Abelino’s and challenge land rights violations at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Social media campaigns are raising awareness of malicious prosecutions, Front Line Defenders have organised international petitions and ActionAid Guatemala, amongst others, has provided direct support to FGT, Abelino and his family.

The immediate goal was to achieve freedom for Abelino. We must also challenge the use of malicious criminalisation to obstruct people's rights. But there is also determination to build pressure for a consultative approach for developing a new agrarian law. Together, with an effective process we can secure indigenous land rights as promised in the Peace Accord more than a decade ago.

The judgment that confirmed Abelino Chub’s freedom has also requested a criminal investigation into the ownership of the contested land. This further reinforces the testimony that the Finca Plan Grande belongs to the Mayan people. It underscores a history of dispossession of the land of indigenous communities.

In this video Claudia Samayoa examines many of the issues raised by Abelino’s case. Why was he was accused? How was his acquittal achieved? What are the implications of this case, and how can human rights defenders and their communities be supported?

Despite this important victory, Claudia Samayoa describes the overall situation for human rights in Guatemala as "very dire and dark." This opinion is supported by a recent report from the UN Human Rights Office.

Constitutional protections are being removed or flouted. Attacks on human rights defenders are increasing. This needs constant monitoring and international solidarity with individuals, communities and organisations to raise awareness and support resistance in Guatemala:

“in order to get a minimal democracy working again.”