Never Give Up: the struggle for a birthright

This is the story of internally displaced people in Uganda and their fight for a land to call home

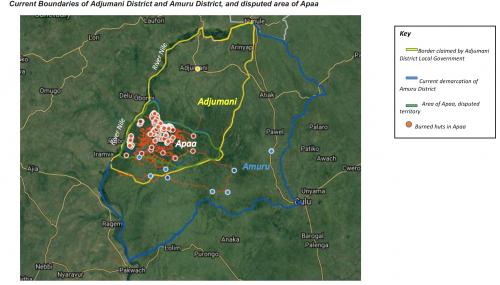

More than 90% of the Acholi people, together with many surrounding communities, were evacuated from their homes into Internally Displace People’s camps (IDP camps) for a decade or more from the mid-1990s as a result of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) insurgency. On return from the camps many communities found their land occupied or otherwise expropriated. In the case of Apaa, an area on the western borders of the Acholi sub-region, returnees in 2006/7 discovered that in their absence the land they had previously lived on had been reallocated from Amuru to Adjumani District and ‘gazetted’ (official demarcated) as East Madi Wildlife Reserve. This wildlife reserve was then leased to a foreign investor, Lake Albert Safaris, for game hunting in a private-public partnership. The community has experienced successive episodes of violent evictions while the controversy over the land is still awaiting resolution.

The UWA assert that they are only following their mandate by removing ‘illegal’ squatters from a protected area. Whatever the rights or wrongs of the boundary dispute, what is clear is that a vulnerable group of people have had their only source of food and livelihoods taken from them and that extreme violence, including death, injury, theft and destruction of property has been used to try to force them away. A report from the Refugee Law Project concludes that, ‘The dispute in Apaa poses a considerable threat to post conflict recovery and local development …The continuous eviction, and displacement in Apaa village has decimated food production and this threatens livelihood in the disputed area’. Those affected suspect that the true motive behind the actions was revenue that could be gained from the hunting franchise and, after the investor abandoned the project, the possibility of mineral extraction in the area. In either case it was convenient to label the residents as squatters and evict them.

Portraying the conflict as a tribal land dispute between Madi and Acholi groups or as a conservation issue has also served to obscure the true causes of the conflict, and justify the heavy-handed security response. While at first evictions were resisted by both Acholi and Madi residents, from 2012 the conflict has become increasingly taken on a communal nature resulting in violent clashes between armed irregular groups. There is strong evidence that senior politicians have been involved in promoting the conflict between communities.

Following the initial evictions when 170 huts were burned in 2010, a High Court injunction was sought in 2011 to prevent further evictions. However, in February 2012 the first deputy Prime Minister of Uganda Gen. Moses Ali (Member of Parliament for part of Adjumani District) ordered further evictions. This resulted in two deaths, many arrests and the destruction of hundreds of homes with up to 6000 people made homeless . In the immediate aftermath the Gulu High Court granted an injunction prohibiting any further evictions while the dispute was being resolved, an order which still stands to today. In June 2012 the President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, promised to find a peaceful solution. However, Gen. Moses Ali MP, the first deputy Prime Minister and an interested party, was put in charge of the Cabinet sub-committee to investigate, resulting in lack of confidence in its independence.

Despite the High Court injunction, the level of violence has increased over the years with massive evictions involving the UWA, the national army (UPDF) and the police. In 2015 another wave of evictions resulted in more deaths and many people with serious injuries. In June 2017 ethnic violence resulted in eight deaths recorded by Lacor Hospital. From late 2017 through to mid-2018 waves of attacks have been conducted by soldiers leaving at least two more people dead (bringing the total during the conflict to at least 18), with hundreds of homesteads burned, livestock and food and crops stolen or destroyed.

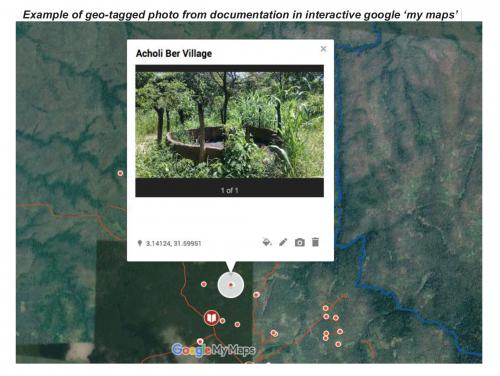

A serious humanitarian situation resulted with families scattered into the bush or setting up temporary shelters in villages and trading centres. A documentation exercise with geo-tagged photographs shows that at least 844 huts have been burned since late 2017.

Basic services, such as schools and health centres have also closed due to the insecurity and lack of clarity around which authority is responsible for delivery in the area. Some facilities are now occupied as shelters for displaced people. An Amnesty International investigation led to a demand for urgent action and brought much needed attention to the situation.

As a result of the humanitarian crisis, ActionAid Uganda has responded both to provide humanitarian relief in the form of tarpaulins for displaced people and to engage with communities to support their fight for their human rights. Meetings were held with community members, CSOs and leaders in order to build capacity for non-violent activism. An evolving strategy of engaging civil society and politicians to find a solution to the crisis was initiated. A meeting was organised with the Paramount Chief of Gulu, the Archbishop of Gulu, many community leaders and CSO representatives and following discussion a delegation including religious leaders, media and an Amuru MP was sent to intervene with the armed forces. Some immediate respite for the residents resulted. A second delegation resulted in soldiers temporarily leaving the area but returning soon after.

Community resistance

Despite the serious nature of the conflict, it only received much public and official attention when the despairing women of Apaa stripped naked to shame a delegation of government officials and surveyors who arrived to impose the new District boundary in July 2015. Anek Karamera, an elder woman of the community describes what brought her to take this drastic action. “I’m one of the women who participated in the nude protest in 2015. My son Okot Alaba was killed in 2014 by Uganda Wildlife Authority during the forceful evictions and I’m still mourning him to this day. I lost over 50 acres of land. My hut was burnt twice. Now I have just roofed my new shelter here on the narrow strip I was given as a refugee, and it is in this shelter I now live with my grandchildren here in Apaa Centre. I keep these burnt belongings as reminders of what happened.”

The increasing attention brought to the situation led to Parliamentary debates but failed to stop the attacks. The President proposed visiting Apaa on 27th June 2018 to talk to the communities. This visit was postponed at the last minute but while families in Lulai area had travelled to attend the meeting in Apaa centre their homes were attacked and destroyed by the army. A second scheduled visit on 5th July was also postponed.

With more than 2000 recently homeless people and faced with apparent official indifference and impunity for the forces acting against them, the communities had to find another route to influence events. On July 11th, after travelling for nearly 100km by foot and lorry, 234 women, children and men from Apaa entered the compound of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN OHCHR) in Gulu in a non-violent action to highlight their predicament.

They were once more displaced from their homes, but this time voluntarily, in order to bring their predicament to the door of the global body mandated to protect human rights. This delegation occupied the UN OHCHR compound for more than a month as part of a considered strategy. Their immediate demand was for the UN body to engage the President to enforce the 2012 High Court injunction, to immediately cease the violent attacks and ensure withdrawal of security forces. If the government failed to respond, their next demand was for the High Commissioner to engage foreign embassies to suspend funding for the Ugandan Government. The response of the UN agency was initially less than welcoming with no direct formal engagement but soon MPs, religious leaders and CSOs were visiting, bringing supplies and holding talks with the delegation.

There were certainly risks associated with a large group leaving their families behind in Apaa with an uncertain welcome ahead of them in Gulu. It was calculated that this UN body would be less likely to confront the delegation violently and would need to engage with the issue. However, the unpredictable logistics of transport, gaining access to the compound and supporting the community through an extended period of occupation needed to be supported on an open-ended basis.

Despite the attempts of the UN agency to cut off sources of support the occupiers refused to leave without action. UN OHCHR claimed it was monitoring and engaging government but was not in a position to make demands of a host government. Different approaches were pursued while the attention the occupation gained kept the media profile of the issue high. Representatives travelled to Kampala for meetings with foreign embassies, the Speaker of Parliament and Uganda’s Land Commission of Inquiry. This resulted in the Commission opening an investigation and the EU and US ambassadors agreeing to raise the issue with President Museveni.

While not publicly taking action, the UN OHCHR country director met with the representatives and verbally assured them that a directive had been issued against any further evictions. However, there were no commitments on how the agency would respond to any renewed attacks. After 36 days, the delegation decided to return home to continue their resistance on the ground.

The national and international pressure brought about has prompted official attempts to find a resolution. The President finally visited Apaa in August 2018 and given the failure of General Moses Ali’s 2012 committee to resolve the issue announced the formation of a new committee under the Prime Minister to decide whether the area should be de-gazetted or the residents resettled elsewhere. He committed to ‘a win-win situation for our people who have been tossed around by liars for so long. Some of our people have died in this confusion’. However, there was no direct consultation with the communities and a fear that those who had participated in the Gulu occupation could be targeted for retaliation. The thrust of the President’s address was not reassuring: ‘Liars told you to go to the UN compound, that the UN will force Museveni, I don’t know, to do what?’ and after reviewing the post-colonial history of the area stated, ‘We, the leaders who came after them know the importance of parks. Parks bring in more money, US$1500m, than coffee, US$500m’. Although assurances were given about withdrawing army units they have actually been strengthened in early 2019 with renewed attacks and a total of more than 900 destroyed huts documented.

On February 11th this year a contingent of armed soldiers and UWA staff undertook a ‘household survey’ and registered 374 households. This exercise was undertaken without any prior consultation, explanation or even forewarning. As agents of the forces who have victimised the community, cooperation was limited and the exercise only took in easily visited homesteads along the main routes through Apaa. A few days later a visit by the President was announced but cancelled again at the last moment. The purpose of all this became clear on 27th February when a compensation package was revealed via the media and immediately rejected by Acholi MPs. It is hard to interpret this as a ‘win-win’ situation as acceptance would result in permanent dispossession of communal land in return for the partial compensation of some households, with no guarantee that equivalent land is available or affordable and no provision for the rest of the community. The rejection of this offer has divided local opinion further. On the Adjumani side, they feel the issue has been settled for once and all, the Apaa residents should accept the compensation and disperse where they will to attempt to buy land elsewhere. Meanwhile, the affected people, having suffered so much and shown brave resistance in the face of apparently impossible forces are equally determined not to accept. The result has been the President rescinding the decision and forming a third committee, under the leadership of the Deputy Speaker of Parliament, which the Apaa community are grasping is a possible lifeline to help resolve the issue in a way that respects their constitutional rights.

As court injunctions against violent evictions have failed to protect them so far, community leaders are considering an appeal to the International Criminal Court if a decision that respects their rights is not delivered and implemented. The community has demonstrated exceptional resilience over the years since their return from IDP camps but will require their leadership and resources to be supported further in the coming months.