Migrant women’s resilience in Spain

Laws that deny rights

In January 2019 Carmen Leigue was arrested, imprisoned and scheduled for deportation by the Spanish state. She was a 65 year old Bolivian woman who had lived in Valencia for 17 years and worked extensively as a carer.

A massive mobilisation of organisations and individuals managed to overturn the action. But the case highlighted the growing precariousness of migrants, particularly women. They are often caught in a web of arbitrarily implemented laws that leave them insecure and vulnerable to exploitation.

In Spain today there are a range of challenges, including racism and violence, that confront migrant women. These challenges come from negative social attitudes, institutional discrimination and a legal framework that fails to protect migrant women’s rights.

The foremost of the laws that migrant women identify as problematic is the Immigration Law. It imposes a number of conditions on women to reside in Spain within the law.

To get a temporary residence permit for arraigo, or social integration, you need a valid identification document and proof of living continuously in Spain for three years. However, it is not always easy to be registered as resident, especially for those with no formal address to be registered at.

Another barrier is the necessity to prove that the applicant does not have a criminal record. This is often not easily to get from the woman’s country of origin and is even often out of date by the time the application is considered.

They need to have a pre-work contract signed by a potential employer at the time of the application. The contact must be for full-time work for a minimum of a year and at an official minimum wage – something few employers are prepared to provide.

As well as all this documentation, an applicant has to provide evidence of family ties or submit a report on the status of their social integration. All these demands need to go between three levels of authority that do not necessarily prioritise the wellbeing of the applicants.

One woman, from Democratic Republic of Congo and resident in Spain for 19 years, observed:

“The social integration (arraigo) permit is a contradiction, because to get it you need a work contract, but without papers there is no contract.

In addition, there are other requirements such as criminal records and not all African countries grant this information.

Some people arrive here after crossing the sea and arrive without a passport, and their entire family has disappeared and this does not allow them to gain their passport."

Becoming 'irregular'

Even if all these onerous conditions are met and the permit granted, it is only valid for 24 months. It has to be renewed, providing evidence of at least 18 months work in that period.

Only after five years of continuous residence is it possible to reach the security of a long-term permit. There are very many pitfalls that can easily result in the immigration status becoming ‘irregular’.

This leaves women vulnerable to many kinds of exploitation in order to avoid being arrested and possibly deported.

In practice, many migrant workers need to live and work in the informal economy for years before getting their first formal contract.

Even then there are many risks of falling into irregularity, with severe consequences. Without formal status it is impossible to gain access to social security. Poor housing and a precarious family life are common.

Women identify needing a formal job contract for their residence permit as one of the biggest problems to confront them. Groups representing their concerns argue that, once residence can be demonstrated, the ‘right to have rights’ should be established.

“The residence permit must be given for the fact of living in the territory, not linked to a contract. That limits a lot, many people to do not have the papers and subsist the best they can.

The residence permit is the first step to regain self-esteem and be able to advance towards dignity in your life,”

argues a Colombian woman who has lived in Spain for 16 years.

Falling into irregularity can lead to arrest and a lengthy period of detention while an inefficient system examines the case.

A 2015 ‘Citizen Security’ Law has worsened the situation. It clearly discriminates against migrants.

All foreign residents must carry and display on demand both their ID from country of origin as well as their status in Spain. For foreigners, ID checks are not just to verify their identity but also their immigration status.

The overwhelming experience is that racial profiling is used in implementing the Citizen Security Law. Checks are targeted on migrant communities and ‘foreign looking’ people in public. They happen on the subway, in call centres and predominantly migrant neighbourhoods.

This is how Carmen Leigue was caught up and threatened with deportation. The fear of these arbitrary checks and the serious consequences acts to severely limit migrants’ freedom of movement, expression and participation.

The regime is even harsher in the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, Spanish enclaves on the Moroccan coast. The law says that foreigners found trying to enter irregularly can be ejected summarily. This violates the Geneva Convention, which forbids sending people back into a situation of danger. This is also known as the "non-refoulement" principle of the Convention.

The arbitrariness of the law has a huge impact on people living in conditions of discrimination and inequality, such as migrants. It leads to denials of basic rights.

A young Honduran woman in Valencia reported to the police a serious armed assault by a man. Eldiario, a left-wing online newspaper, reports ‘Laura’ as stating:

“ … the first thing that occurred to me is to go to the police, without imagining that when I got to the police station I would have more problems… They started to tell me that I was living illegally in the country and they were going to open an expulsion order…”

The police were more concerned with immigration status than protecting Laura from violence.

‘Laura’ claims she fled Honduras after her brother was murdered in gang violence. But she said she had no confidence in the Spanish asylum process and feared being unable to work and support herself if she applied. This lack of confidence appears to be justified.

Despite many migrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea, few have made asylum claims. There is a lack of access to information and to the process of making such claims.

For example, fewer claims from Syrian migrants were registered in 2018 than in 2017 as legal and safe ways to access asylum procedures are closed down. One researcher comments:

“The system is collapsed, showing at the same time a lack of political will and technical incapacity: Spain doesn’t see itself as an asylum country: we are not prepared, and it seems that we don’t want to be prepared.”

This doesn't only reflect the situation in Spain. It's also the closing down of humanitarian routes and the failure of the European Union to agree a fair system among its members.

Solidarity and visibility

For the vast majority of migrant women, the opportunities when they initially arrive in Spain are mostly domestic service. This is the case whatever their qualifications and training. Domestic work is low paid, unregulated and women are vulnerable to violence and abuse by employees. Women are understandably reluctant to report such abuse.

Such social conditions of isolation and vulnerability conspire against collective action. But solidarity is growing, as organisations and networks have developed among women to fight for their individual and collective rights.

For example, Servicio Doméstico Activo (SEDOAC) is an organisation of women of many different nationalities. They advocate for the rights of all domestic and care workers.

They are asking for rights to unemployment benefits, protection from harm and work place inspections among other demands. SEDOAC has just opened the Centre for the Empowerment of Domestic and Care Workers in Madrid, funded by Madrid City Council. It aims to provide the support that domestic and care workers need to fight for respect for their work and dignity in their working conditions.

A woman from El Salvador, who has been resident in Spain for nine years explains:

“We are fighting for the recognition of domestic work as something necessary and dignified, but unfortunately society and people are responsible for making it unworthy, low and despicable and so the people employing domestic workers do the same and transform it into slavery.

Becoming aware of that was for me the first step to reverse the approach, and that has been one of my reasons to fight: my activism goes further than just payment for my work, this has strengthened me, because this became like something where I feel worthy.

It is hard to say it, but people are responsible for making you feel that way"

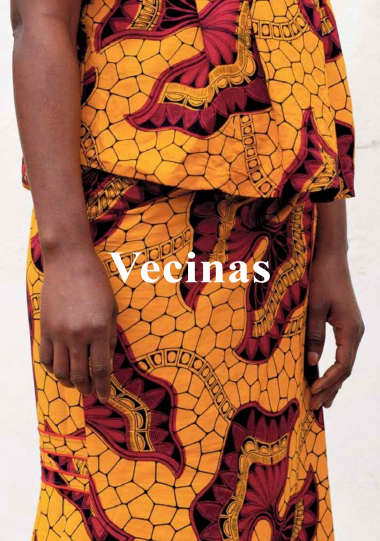

Among many other initiatives, two projects have also evolved to bring the stories of migrant women to light. They confront prejudices and stereotypes and value their contribution to society. Vecinas, (Neighbour) is a project produced in 2015 by Malian women in cooperation with Brazilian photographer Angélica Dass, the Malian High Council in Spain and the support of Alianza por la Solidaridad.

Yo Soy Somos, (I Am We Are), that Angélica Dass and Alianza developed from the Vecinas project, is a newspaper and exhibition that shares different women’s stories. The pages of the paper have been made into panels that have been exhibited in public spaces.

Sharing their stories in this way contributes to migrant women developing their self-confidence. It also encourages the host society to see them less as a problem or an issue and more as fellow human beings with dignity and rights.